Tommy Robinson: the voice of Britain's far-right

The best-known figure on the UK’s extreme-right has been accused of playing a part in inciting the recent riots

On 29 July, the day of the attack on a group of young girls in Southport, far-right influencer Tommy Robinson repeated on X the false rumour that a Muslim asylum seeker who'd arrived on a Channel boat was the culprit. On the site, where he has nearly one million followers, he repeatedly linked the stabbings to the Muslim community, and said that the Government was "gaslighting" the public about the events. In the days after the attack, his X posts received an average of around 54 million daily views.

Robinson has become the figurehead for Britain's de-centralised, or "post-organisational" far-right: rather than trying to run a political party, he builds support by spreading his beliefs online. His ideas clearly resonate with many Britons. Several thousand supporters marched in his "patriotic rally" in London on Saturday 27 July, the largest far-right demonstration since the collapse of the EDL. And he attracts vocal support and funding from the US, where he has become a darling of the Trumpian and libertarian Right.

Who is Tommy Robinson?

The 41-year-old's real name is Stephen Yaxley-Lennon. He grew up in Luton, in Bedfordshire, a town with a large Muslim minority. He was an apprentice aircraft engineer at Luton Airport, but in 2005 he assaulted an off-duty police officer during a drunken row, which resulted in a 12-month sentence. In 2004, he had joined the far-right British National Party. By that time, he'd had a long association with football gangs linked to Luton Town FC (his nom de guerre was supposedly taken from a notorious Luton Town hooligan). In early 2009, the Islamist extremist group al-Muhajiroun protested noisily in Luton against a parade by members of the Royal Anglian Regiment, who were returning from service in Afghanistan. In response, Robinson and others linked to football gangs formed the English Defence League (EDL), which held anti-Islam demonstrations across England.

Subscribe to The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

What happened to the EDL?

In its first few years, it grew fast, holding protests in areas with big Muslim populations, sometimes thousands strong, at which there were frequent violent clashes. Then in the early 2010s, the EDL declined amid internal divisions, and after it was revealed that members had links to the Norwegian white supremacist mass murderer Anders Behring Breivik. Robinson was convicted for assaulting a fellow member in 2011, and received a suspended sentence. In 2013, he underwent an unexpected political conversion and left the EDL, citing the "dangers of far-right extremism", supported by the anti-extremist think-tank Quilliam. This proved short-lived: Robinson reverted to far-right politics, with an attempt to set up a UK branch of the European counter-jihadist organisation Pegida.

What has Robinson done since?

He has set himself up as a journalist and online influencer. From 2017, he was a correspondent for Rebel News, a Canadian far-right website, and made films about the "grooming gangs" run by Asian men in Northern towns and cities. While reporting he has twice been convicted of contempt of court for making prejudicial public claims about grooming cases. In 2019, he ran as an independent candidate for North West England in European elections, receiving only 2.2% of the vote. Since then, he has turned away from electoral politics.

What does he believe in?

The two main themes of his thinking are opposition to immigration and to Islam. As he put it in a recent interview: "We're losing our culture. We're losing our identity. We're being replaced. We're becoming minorities in most major cities. We're being driven out of our own country, our own towns." In 2016, he said: "I'm not far-right, I'm just opposed to Islam. I believe it's backward and it's fascist." He made this argument in detail in "Mohammed's Koran: Why Muslims Kill For Islam", a 2017 book he co-wrote. His social media feeds return continually to immigrant – and particularly Muslim – criminality.

Robinson also believes that Western elites have plotted against ordinary people to allow this immigration to occur. He also often states that Britain has a "two-tier police force" that comes down "like a ton of bricks" on white miscreants, but is soft on migrant criminals. Robinson believes that the mainstream media has connived in this by failing to report on these issues fairly.

Ought his views to be censored?

In general, Robinson stops short of directly inciting violence, and has never been prosecuted for that. But his influence has long been linked to far-right violence. The wife of Darren Osborne, who carried out the attack on Finsbury Park mosque in 2017, stated that Osborne had "been watching a lot of Tommy Robinson stuff on the internet", and had been "brainwashed". Robinson was banned from Facebook and Instagram in 2019, for "posting material that uses dehumanising language and calls for violence targeted at Muslims". In 2018, he was banned from Twitter for violating its rules on "hateful conduct": he had, to take only one example, liked a post calling on people to "make war" on Muslims. But, following Elon Musk's purchase of the site, Robinson's account was reinstated late last year.

Police are allegedly investigating his role in the riots. He could be vulnerable under the new Online Safety Act, which makes it an offence to convey false information likely "to cause non-trivial psychological or physical harm".

What about Robinson's legal woes?

On top of his two assault convictions, in 2013 Robinson was jailed for ten months for travelling to the US on another man's passport. The following year, he was sentenced to 18 months for mortgage fraud. In 2017, he was convicted of contempt of court: he had recorded a report outside a trial in Canterbury Crown Court, in which he described the defendants – before the verdict was reached – as "Muslim child rapists". He was given a suspended sentence, which became a nine-month jail sentence after he reported live outside Leeds Crown Court during a similar trial; he not only once again broadcast prejudicial comments, but also confronted the defendants, risking the trial's collapse.

In July 2021, Robinson was ordered to pay £100,000 in damages for libelling Jamal Hijazi, a 15-year-old Syrian refugee who had been badly bullied at his school in Huddersfield; Robinson had claimed, baselessly, that the boy "violently attacks" English girls. He then repeated these claims in his film, "Silenced", which portrays him as a free-speech martyr. Robinson was due in the High Court in late July, because he had broken an injunction preventing him from releasing the film. Instead, he left the UK for Cyprus; he has yet to return. Robinson's tax affairs are also reportedly under investigation.

Create an account with the same email registered to your subscription to unlock access.

Sign up for Today's Best Articles in your inbox

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

-

The week's best photos

The week's best photosA helping hand, a rare dolphin and more

By Anahi Valenzuela, The Week US Published

-

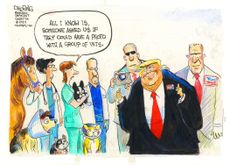

Today's political cartoons - August 30, 2024

Today's political cartoons - August 30, 2024Cartoons Friday's cartoons - seasoned vets, football season, and more

By The Week US Published

-

'Harris gains slim lead'

'Harris gains slim lead'Today's Newspapers A roundup of the headlines from the US front pages

By The Week Staff Published

-

Thailand: heading for a 'political inferno'?

Thailand: heading for a 'political inferno'?Talking Points Hopes of change fading as establishment moves to dismantle reformist Move Forward party

By The Week UK Published

-

The most consequential presidential debate moments in modern history

The most consequential presidential debate moments in modern historyThe Explainer From Joe Biden to Ronald Reagan and everyone in between

By Justin Klawans, The Week US Published

-

The Iraqi bill to lower the age of marriage for girls to nine

The Iraqi bill to lower the age of marriage for girls to nineThe Explainer Politicians and activists are protesting the conservative bill, which would give religious leaders more power over personal affairs

By Abby Wilson Published

-

What did Kamala Harris accomplish as a California senator and attorney general?

What did Kamala Harris accomplish as a California senator and attorney general?The Explainer How the Democratic presidential candidate's state-level achievements might inform her national ambitions

By Rafi Schwartz, The Week US Published

-

The United Nations' possible ties to the attack on Israel

The United Nations' possible ties to the attack on IsraelThe Explainer Nine staff members from the UN's Palestinian refugee program may have been involved

By Justin Klawans, The Week US Published

-

Venezuela votes: 'the mother of all stolen elections'

Venezuela votes: 'the mother of all stolen elections'Talking Points Nicolás Maduro has pulled off a breath-taking steal at the ballot box, but his power increasingly relies on foreign allies

By The Week UK Published

-

The future for Hamas under Yahya Sinwar

The future for Hamas under Yahya SinwarThe Explainer Choosing hardline 'butcher' as political leader signals Gaza as centre of group's power, but imperils ceasefire negotiations

By Harriet Marsden, The Week UK Published

-

What did Donald Trump accomplish as president?

What did Donald Trump accomplish as president?The Explainer These are the achievements he can point to as he asks voters for a second term in office.

By Rafi Schwartz, The Week US Published